Shakespeare’s plays, apart from changing theater forever, also shaped how people talk today. He experimented with language, pulled from other tongues, added prefixes and suffixes, and combined words in ways no one had seen before. Scholars estimate that over 1,700 words first appeared in his writing. Here are 15 standout examples that slipped into everyday English.

Swagger

Mistress Quickly in Henry IV, Part 2, refuses to let any “swaggerers” through her door, and suddenly a whole new word exists. Back then, it captured the image of someone stomping about with a cocky sway. These days, swagger shows everywhere—from athletes celebrating wins to fashion brands describing their style.

Addiction

When the Bishop of Canterbury in Henry V mentions the king’s “addiction” to lighthearted pursuits, he isn’t talking about substance dependence. In that context, it meant a tendency or strong preference. Over time, the meaning grew sharper and linked to habits or substances that grip someone’s life.

Eyeball

Shakespeare needed a vivid way to describe the rounded shape of the organ itself, not just sight. The word “eye” was old, but “eyeball” was brand new when it appeared in The Tempest. That single inventive tweak gave English a more precise term.

Lonely

Before Coriolanus, English speakers didn’t have a single word that captured the ache of being without company. Scholars believe he merged “lone” with the suffix “‑ly” to create it. It’s remarkable how a playwright’s need for emotional accuracy gave generations a word that still hits hard in modern conversations.

Fashionable

“Fashionable” pops up in Troilus and Cressida as Ulysses sizes up the fleeting nature of popularity. At the time, it captured a sense of whatever was in style, not just clothes. Over the years, it became the go-to word for anything that feels current—whether you’re talking about a jacket or the latest gadget.

Bedazzled

When Shakespeare used “bedazzled” in The Taming of the Shrew, he was describing the effect of intense light on someone’s eyes. That little tweak—adding “be” to “dazzled”—gave English a new way to talk about being completely dazzled, whether by sunlight or by something flashy and eye-catching.

Dawn

Before Shakespeare, English often used “daybreak” or “sunrise.” Dawn gave writers and speakers a shorter, softer word. It’s now so common we rarely pause to consider its literary birth. That single creative choice brightened countless sentences and headlines.

Bandit

The term “bandit” stuck and became a staple in adventure tales and Western movies centuries later. Henry VI includes one of the earliest English uses borrowed from the Italian “banditto.” In Shakespeare’s world, it described an outlaw or highway robber—a common fear for travelers.

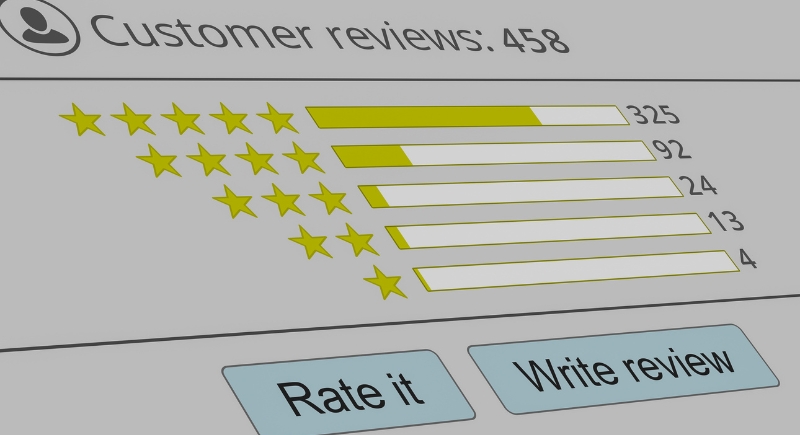

Critic

Today critics fill newspapers, review films, and dominate social media comment sections, but it was in Love’s Labour’s Lost where Shakespeare introduced the term “critic,” aimed at someone too eager to judge. Before that, English didn’t have a neat single word for such a person.

Outbreak

Polonius in Hamlet refers to the “outbreak of a fiery mind,” to illustrate sudden bursts of reckless energy. “Outbreak” was a new way to describe a rapid eruption, whether of thoughts or actions. Centuries later, the word became essential for describing disease surges or social unrest.

Frugal

When a character in The Merry Wives of Windsor talks about being “frugal,” he means careful with money or resources. Shakespeare’s audience would have understood thrift, but “frugal” gave the idea a crisp, new label.

Cold-Blooded

In King John, Constance throws out “cold-blooded” to call out a lack of feeling. Back then, people thought warm blood meant passion, so calling someone cold-blooded stung. Now, the phrase is still used when talking about acts done with zero emotion, especially in stories about crime or betrayal.

Auspicious

Modern speakers often use this word for weddings, launches, or milestones to mark good beginnings. That sense of hopeful fortune has stayed intact since Love’s Labour’s Lost, where Shakespeare uses “auspicious” to mean promising or favorable. He tapped into Latin roots to craft a term that sounded optimistic.

Undress

The Taming of the Shrew includes one of the earliest English uses of “undress,” referring simply to removing clothes. Before this, writers often used phrases like “do off garments.” His shorter version felt natural and stuck.

Majestic

In Henry VIII, characters describe something as “majestic” to evoke grandeur and dignity. Although earlier terms hinted at greatness, this word delivered a sharper, more regal tone. Modern English still uses it to describe mountains, architecture, or even a memorable performance.