Some stories stay relevant, no matter how long ago they were written. They’ve shaped public thought, changed how people understand identity, and challenged long-held beliefs. These titles carry historical, political, and personal weight.

Each book on this list has sparked discussion long after its release and continues to be referenced in classrooms, essays, and conversations about meaning, power, and memory.

To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

Published in 1960, To Kill a Mockingbird examines racial injustice through a Southern courtroom case set in the 1930s. Atticus Finch defends a Black man accused of assault, while his daughter Scout observes the town’s reaction. To Kill a Mockingbird remains a reference point in conversations about law, race, and character education across generations.

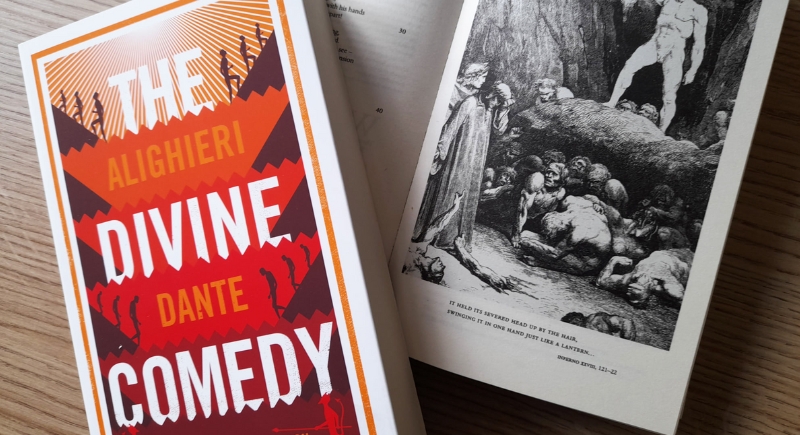

The Divine Comedy – Dante Alighieri

Reading The Divine Comedy means following a guided journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, structured around moral order and spiritual progression. The poem uses vernacular Italian instead of Latin, which means it’s more accessible to readers outside the elite. Dante combines historical and imagined figures to reflect on justice, power, and personal failings.

Don Quixote – Miguel de Cervantes

Calling Don Quixote influential doesn’t quite cover it. Cervantes’ novel laid the groundwork for what a modern story could be. Its impact stretches centuries by shaping fiction, theater, film, and how writers think about character. You’ll find echoes of it in everything from literary metafiction to satirical comedy, without realizing where the roots begin.

The Odyssey – Homer

Written in the 8th century BCE, The Odyssey follows Odysseus as he attempts to return to Ithaca after the Trojan War. Along the way, he faces shipwrecks, mythical creatures, and shifting allegiances. Its nonlinear structure, vivid imagery, and focus on endurance and recognition have made it a cornerstone in the study of epic storytelling.

Pride and Prejudice – Jane Austen

Elizabeth Bennet knows her mind, but reading people proves harder than she expects, especially when it comes to Mr. Darcy. Their misunderstandings and slow recognition unfold through sharp dialogue and social missteps in Pride and Prejudice. Beneath the surface, Austen tracks how status, gender, and assumptions shape relationships through observation and the weight of unspoken rules.

1984 – George Orwell

Conversations about surveillance, censorship, or digital manipulation almost always circle back to 1984. Orwell built a framework for understanding how power reshapes truth. Ideas like “doublethink” and “Big Brother” still carry weight in political commentary and everyday language.

Little Women – Louisa May Alcott

If you’re drawn to stories about growing up, sibling tension, and figuring out who you want to be, Little Women is the book to read. Alcott’s portrayal of the March sisters gives each one space to wrestle with ambition, duty, and personal change, without forcing tidy resolutions. It’s especially compelling for people interested in how family dynamics shape personality over time.

The Great Gatsby – F. Scott Fitzgerald

This 1925 novel focuses on the pursuit of wealth and status in New York’s Jazz Age. Jay Gatsby builds an elaborate life in hopes of regaining a lost relationship. Fitzgerald uses minimalist language to explore identity, self-invention, and social limitation. The book gained prominence after Fitzgerald’s death and now appears on most high school and college reading lists.

Beloved – Toni Morrison

Beloved revolves around a haunted house, but the ghost in it is not real; rather, a physical form of memory, guilt, and unfinished mourning. Morrison uses the supernatural to force a direct encounter with it. All elements carry layered meaning, from names to silences.

The Book Thief – Markus Zusak

The Book Thief hands narration over to Death as a quiet observer of wartime humanity. Liesel, a young girl in Nazi Germany, discovers stolen books as her only steady source of comfort and control. Zusak disrupts the timeline, inserts commentary without pause, and combines tenderness with brutality in ways that rarely stick to convention.

All the Light We Cannot See – Anthony Doerr

In war-torn Europe, two teenagers—one blind, one trained for battle—move through parallel paths shaped by conflict and chance. Marie-Laure lives in occupied France; Werner is sent there as part of the German military. The author avoids sentimentality and uses the format to emphasize how small moments carry meaning during chaos.

The Lovely Bones – Alice Sebold

The Lovely Bones is told from the perspective of a 14-year-old girl watching from the afterlife. It examines how violence shatters a family and how each member copes with loss. The novel became widely discussed for its unflinching portrayal of trauma and its haunting vision of the space between life and what follows.

The Call of the Wild – Jack London

For readers drawn to survival stories, Buck’s transformation leaves a powerful mark. Jack London’s prose centers the novel on themes of instinct, power, and the pull of the primitive. As Buck is taken from domestic comfort into the brutal Yukon, his shift from pet to pack leader unfolds with raw clarity. Those interested in nature writing or animal behavior are especially captivated by this piece.

The Alchemist – Paulo Coelho

The Alchemist is praised for its simplicity and criticized for the same. Many reviews focus on its impact during periods of uncertainty or transition, calling it a guide rather than just a novel. Some dismiss the prose as overly plain, but others find that clarity is part of its appeal.

Crime and Punishment – Fyodor Dostoevsky

You may have been assigned Crime and Punishment in school and struggled through its dense interior monologues, but there’s a reason it keeps showing up on syllabi. Dostoevsky uses the character’s unraveling to explore guilt, punishment, and moral reasoning. The narrative spends more time inside Raskolnikov’s thoughts than on external action.

Their Eyes Were Watching God – Zora Neale Hurston

Hurston’s novel follows Janie Crawford as she moves through marriages, storms, and self-discovery in early 20th-century Florida. Instead of bending to society’s expectations, Janie searches for her voice and horizon. The book blends rich dialect, lyrical narration, and fierce independence, making it a landmark in African American and feminist literature.