King Tutankhamun’s tomb changed archaeology forever, but his life still leaves researchers grasping for answers. DNA testing, CT scans, and royal records have helped piece together some fragments. Yet even basic facts—who ruled before him, how he died, or whose tomb he ended up in—are unsettled.

A century after his rediscovery, Tut continues to raise questions no one can confidently answer.

His Mother’s Name Never Appears in Records

DNA testing helped identify Tutankhamun’s mother, but no one knows her name. Her body, discovered in tomb KV35, shows she was the full sister of the man in KV55—Tut’s father. Akhenaten had several sisters, all known by name, yet no inscription ever connects any of them to this mummy.

The Succession Before His Reign is Disputed

Tutankhamun came to power around age nine, but who ruled before him remains a matter of debate. Two names—Neferneferuaten and Smenkhkara—appear briefly in artifacts from that period. Some inscriptions use feminine grammar, raising the possibility that Nefertiti ruled under a different name.

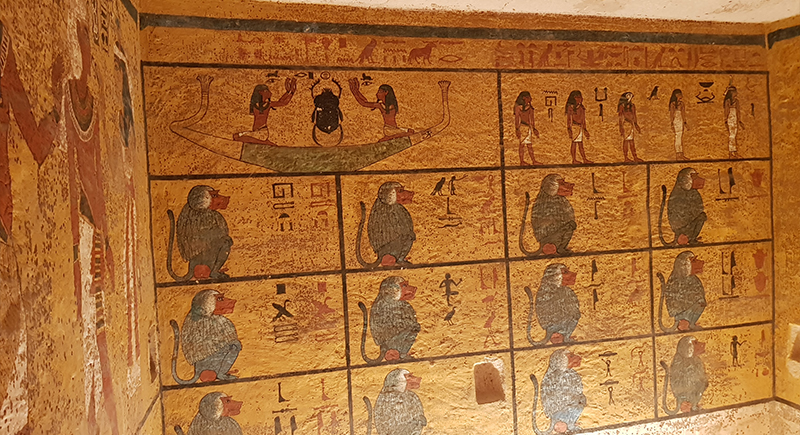

His Burial Chamber Doesn’t Match Royal Standards

Tut’s tomb has puzzled experts for decades. Its small size and incomplete decoration don’t align with what pharaohs usually received. Only one room features painted walls, and many of the items inside appear reused, with altered names and mismatched styles. These signs suggest the tomb was never built for him.

Sweeps Suggest There Could Be Hidden Rooms

In 2015, radar scans behind the tomb’s painted walls picked up unusual voids. Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves proposed that his final resting place might connect to a hidden space, possibly intended for another royal figure. He believed the original tomb could have belonged to Nefertiti.

Radar Results Failed to Authenticate a New Tomb

Follow-up scans yielded mixed results. Some detected architectural features; others came back inconclusive. The limestone bedrock in the Valley of the Kings can interfere with radar and create unclear or misleading readings. Without excavation, researchers haven’t been able to prove or disprove the presence of a second chamber.

Tutankhamun’s Father Might Not Be Akhenaten

Credit: flickr

The body found in tomb KV55 shares genetics with Tutankhamun and has been identified as his father. For years, many assumed this was Akhenaten, Tut’s acclaimed father, based on royal symbols found in the tomb. But key details don’t align. The inscriptions are damaged, names appear altered, and some features don’t fit Akhenaten’s known profile.

He Suffered from Multiple Serious Health Conditions

Living with multiple health conditions likely shaped the young ruler’s daily experience and limited his physical abilities. Scrutiny of his corpse revealed a clubfoot, spinal irregularities, and bone deterioration linked to Köhler disease. DNA analysis also confirmed he had malaria. More than 100 walking sticks were found in his tomb, many visibly used.

No Single Cause of Death Has Been Confirmed

The strongest theory about Tutankhamun’s death centers on a devastating leg injury. Analysis of his body uncovered a serious break near his left knee—an injury severe enough to expose bone and cause rapid infection. The fracture shows no evidence of healing, which points to it occurring shortly before death.

His Injury May Not Match the Chariot Use

Many assume the leg fracture came from a chariot accident. The tomb includes ceremonial chariots and hunting gear, which suggests an active lifestyle. But his foot condition likely made chariot riding difficult or painful. Some researchers think he couldn’t have managed the balance or speed required for such an activity.

No One Knows Who Sent the Hittite Letter

Hittite records mention a surprising letter: an Egyptian queen asked the king to send a son to marry her after her husband died. She said she had no heir. Scholars debate who sent it. Ankhesenamun, Tutankhamun’s widow, seems likely, while others believe that it could have been Nefertiti.

Ankhesenamun’s Fate Stays Undocumented

Following the burial of the king, Ankhesenamun, his half-sister, vanished from all surviving records. A ring inscribed with her name and that of Aye hints at a possible marriage, but its private sale and lack of archaeological context make it difficult to verify. Two unidentified female mummies in KV21 have been considered potential matches, though blood tests are still inconclusive.

The Transition After Tut’s Death Lacks Clarity

Once Tut had been laid to rest, Aye, a high-ranking court official, took the throne. He may have done so by marrying Ankhesenamun or by leveraging his role as a senior court figure. But his reign was brief, and he was soon replaced by General Horemheb. The exact steps of this political transition were never documented.

Two Mummified Fetuses Were Laid to Rest with Him

Inside the tomb of the pharaoh, archaeologists found two intricately crafted coffins holding the remains of female fetuses. Tests disclosed they were daughters of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun, likely lost in late pregnancy. Their burial indicates they were accorded royal status despite never living.

Nefertiti’s Final Years Are Undocumented

Nefertiti, wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten, appeared prominently during Akhenaten’s reign and then disappeared. Some suggest she ruled later as Neferneferuaten, a figure mentioned in inscriptions that use feminine forms. Others think she died earlier or was removed from power. Despite global fascination with her legacy, historians still lack the physical evidence needed to corroborate her final years.

The “Mummy’s Curse” Was a Media Invention

When Lord Carnarvon died shortly after Tut’s tomb was opened, rumors of a curse spread quickly. Reporters claimed an inscription warned of death, but no such text was ever found. Later studies reviewed the lifespans of those present during the excavation. Their death rates matched average patterns.