She’s often known as “the woman who said no” to making one of history’s most infamous objects. Lise Meitner, co-discoverer of nuclear fission, made a deliberate and moral choice that shaped her legacy. This article breaks down fifteen vivid snapshots of her life.

Early Talent in Physics

Lise Meitner, born in Vienna in 1878, had a sharp scientific mind early on. She studied physics at a time when few women did and studied advanced topics like thermodynamics and radioactivity. This led her to the University of Berlin, where she earned one of Germany’s first doctoral degrees among women physicists.

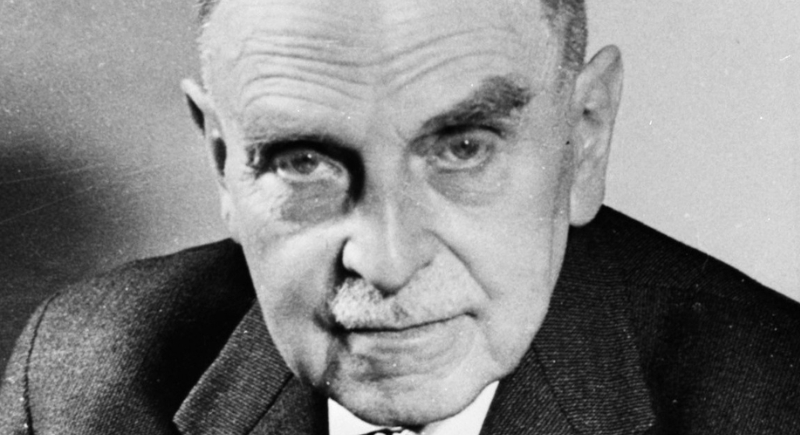

Partnership with Otto Hahn

Meitner and chemist Otto Hahn formed a uniquely effective tandem at Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. She tackled theoretical questions; he managed the experimental work. Many of their experiments remained pivotal even after Meitner fled Germany. Their scientific choreography—one theorist and one chemist—became central to unlocking nuclear fission.

Escaping Nazi Germany

By the mid-1930s, rising antisemitism in Germany threatened Meitner, who had Jewish ancestry. She relied on a secret network of colleagues to help her escape. In the summer of 1938, Meitner fled to Sweden. She left behind her Berlin lab but maintained contact with Hahn through letters and phone calls.

Hidden Collaborations from Sweden

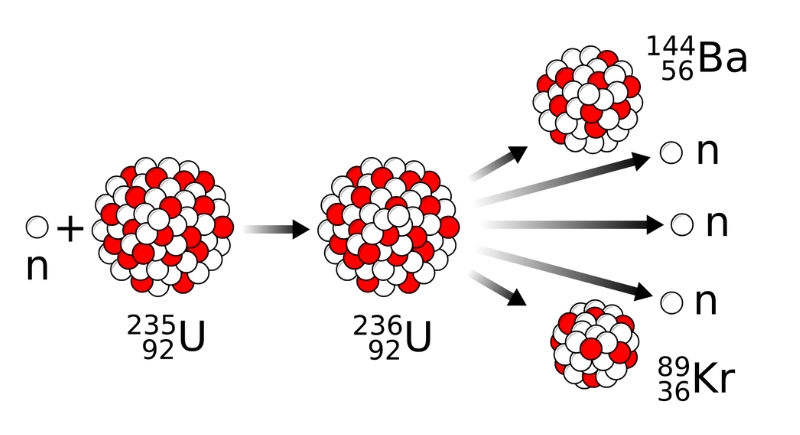

Meitner didn’t stop collaborating. While living in Sweden, she continued analyzing Otto Hahn’s findings, even though communication was slow and coded. She assessed puzzling results during secret meetings, like the unexpected appearance of barium in neutron-irradiated uranium. She helped place the theoretical pieces needed to define nuclear fission.

Naming “Fission” with Frisch

In December 1938, Meitner and her nephew, Otto Frisch, worked through Hahn’s puzzling data to develop a theoretical explanation. They coined the term “fission,” referencing biological cell division. Their paper appeared in Nature on February 11, 1939, in which they framed the nuclear process that would rock the world.

Nobel Prize Controversy

History felt a bit unfair when only Otto Hahn received the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission. Meitner’s exclusion sparked debate among scientists. Though she maintained her usual calm restraint, this oversight underlined the recognition gap women in science often faced.

Humanitarian Convictions from WWI

Long before nuclear fission, Meitner volunteered as a nurse during WWI. She witnessed human suffering firsthand, which deeply influenced her ethical views toward science. These experiences fostered a lifelong wariness of weaponized science. That compassion would later fuel her refusal to assist with conflict development.

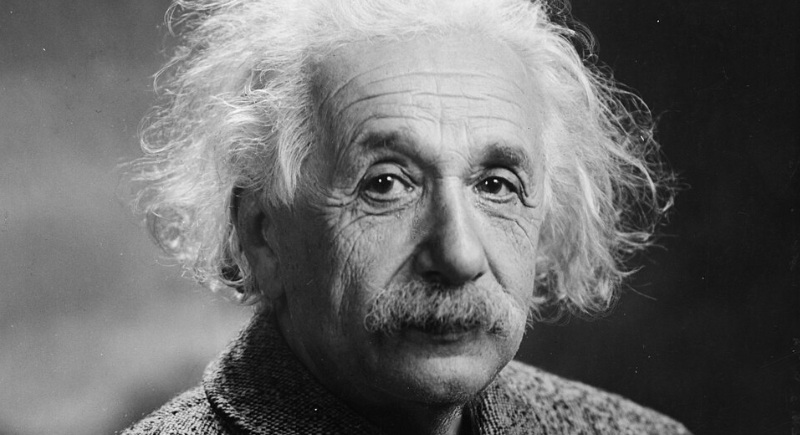

Turning Down Einstein’s Invitation

As the Manhattan Project took shape, Meitner received overtures to join the effort. Along with many European émigré scientists, she received paperwork and invitations, but she categorically declined. She told colleagues she had “nothing to do with a bomb.” In doing so, she laid a line between scientific innovation and ethical responsibility.

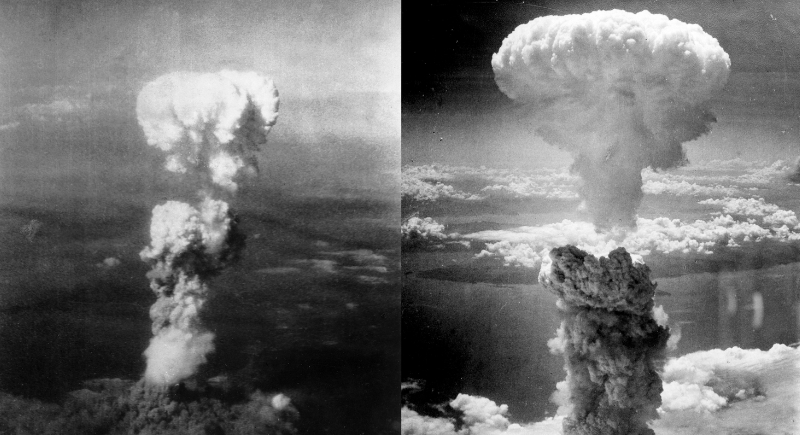

Misattributed Fame in Media

After Hiroshima, the public spotlight fell on Meitner—though inaccurately. Some newspapers incorrectly credited her with building the instrument. Headlines in Time and Stockholm Expressen exaggerated her role. Instead, she responded by distancing herself publicly and reiterating that she’d “have nothing to do with a bomb.”

Hollywood Offers She Refused

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer approached Meitner to feature her in the film The Beginning or the End. She reviewed the script, found it “nonsense from the first word to the last,” and rejected it. Beyond that, she even gave power of attorney to friends so they could block her portrayal.

U.S. Tour in 1946

January 1946 found Meitner in American lecture halls. Despite her stance, she was welcomed with enthusiasm. She spoke at universities, met President Truman at a Woman’s Press Club banquet, and answered tough questions about the situations.

Philosophy of Objectivity

Meitner often described science as a path to “selflessness, truth, and objectivity.” In 1953, she reflected on how understanding reality—warts and all—helped foster deep curiosity. It wasn’t a protest against military science so much as a belief in empirical honesty.

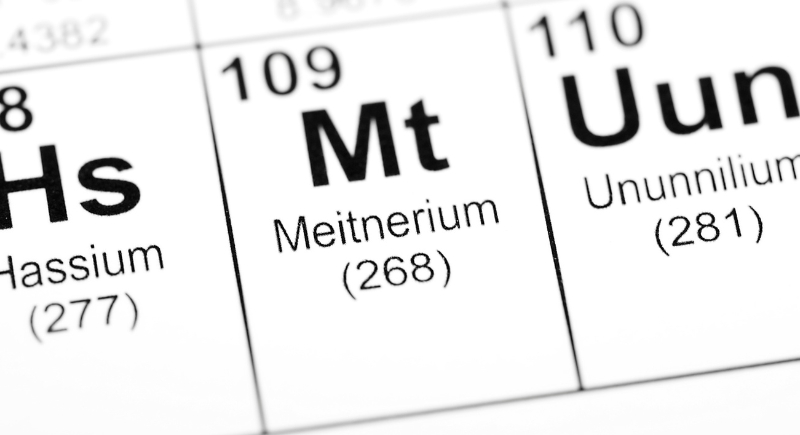

Legacy in Science and Ethics

Today, Lise Meitner lives on through honors like the element meitnerium (element 109) and institutions named after her. Beyond that, she remains a moral exemplar. Her career highlights the tension between scientific discovery and ethical responsibility—still very relevant in nuclear debates today.

Cultural Rediscovery

Decades after her passing, Meitner’s story has seen a renaissance. Biographers combed archives and historians spotlighted her contributions. She was portrayed in modern narratives, and public memory has begun correcting historical oversight. While she avoided fame in life, today’s audiences are recovering her contributions and celebrating her principled stance.

Friendly Reminder for Modern Scientists

Meitner’s choice still resonates. She stepped back when asked to join the bomb project and refused to cross a line she set for herself. Her story challenges scientists to weigh their work carefully. Progress isn’t neutral. Sometimes, saying no is the most lasting contribution you can make.