A lot of what’s on the human body today is leftover from a different era. When early humans lived outdoors, hunted, and faced the elements, traits like heavy body hair and strong jaws helped with survival. Over time, as people started cooking food, building shelter, and using clothing, those features mattered less. Some faded away, and others stuck around, even though nobody relies on them now.

Today, science tracks these outdated features and predicts which ones will likely vanish as we continue to evolve in modern conditions.

Body Hair

Early humans needed body hair for warmth and limited protection. But now its purpose seems to have faded with fire, shelter, and eventually clothing. Now, thick hair offers no survival advantage. Eyebrows catch sweat, and facial hair plays a role in expression, but arms, legs, and torso hair play no active role.

Wisdom Teeth

Chewing doesn’t require a third set of molars anymore, yet many people develop them. Wisdom teeth tend to erupt in late adolescence, often without enough space to grow correctly. They frequently become impacted and lead to gum infections, jaw pain, or pressure on nearby teeth.

Ear-Wiggling Muscles

Before speech, mammals used rotating ears to detect predators. Humans inherited the same muscles, but the role dropped off. Only a few people can still move their ears slightly, and the motion doesn’t improve hearing. Most brains no longer send signals to activate these muscles at all.

Goosebumps

The goosebump reflex would help trap heat or make humans appear highly threatening by lifting thick body hair. That worked when we had actual fur. Though these muscles continue to flex, the effect means little. We don’t need hair to retain warmth anymore, and we don’t intimidate others by puffing up.

Plantaris Muscle

The plantaris muscle, located behind the knee and extending into the calf, previously supported grasping movements in primates. Its original function helped with foot control in tree-dwelling environments. However, it shows no meaningful contribution to leg strength or stability.

Appendix

Removing an appendix rarely affects long-term health, which highlights how unnecessary the organ has become. While it may assist with maintaining certain gut bacteria, the involvement remains limited and nonessential. Inflammation is common and can escalate quickly without treatment. Because the risks outweigh the unclear benefits, surgical removal is often recommended.

Toes

Walk barefoot on rocky ground and you’ll understand why toes mattered to our ancestors. They helped with grip and balance, especially when feet met uneven earth all day. Shoes changed everything. These days, most balance comes from the ball of the foot and the big toe. The pinky toe does so little for movement or stability that some people wouldn’t notice if it disappeared.

Coccyx (Tailbone)

Breaking the coccyx can make something as basic as sitting feel unbearable for weeks, yet doctors can’t do much beyond recommending cushions and time. For human ancestors with tails, this bone formed the anchor for balance and coordination during movement through trees.

Neck Rib (Cervical Rib)

A cervical rib forms near the base of the neck and appears in less than one percent of people. Doctors view it as a developmental error rather than a useful structure. Since it increases health risks and doesn’t assist with anything, future human anatomy may eliminate it entirely.

Male Nipples

Embryos follow a shared developmental process in the initial stages of pregnancy. Nipples form before biological differences between males and females take shape. In males, they remain but have no practical objective. Some studies suggest they may be shrinking, but they persist because they cause no major harm.

Palmaris Longus Muscle

Climbing requires powerful forearm muscles, especially in activities like rock climbing or gymnastics, where grip strength matters. But one long, thin muscle once used for that purpose—palmaris longus—adds nothing noticeable to modern performance. It served early humans who relied on their hands to swing or climb.

Paranasal Sinuses

Some people are born with very small paranasal sinuses—or none at all—and show no health issues because of it. That absence raises questions about what these air-filled cavities actually do. Theories about their value include helping with voice resonance or regulating air temperature, but none are conclusive.

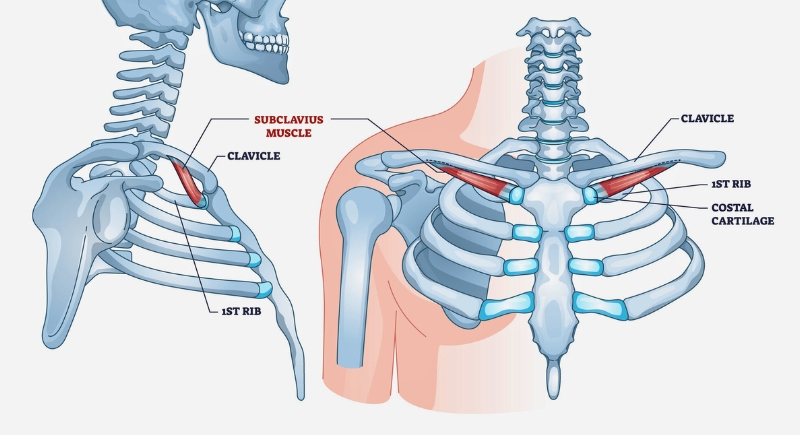

Subclavius Muscle

Weight-bearing movement in four-legged animals depends on shoulder stability during walking, climbing, or jumping. The subclavius muscle helped secure the collarbone to the ribcage, supporting each stride. But as we walk upright and no longer place weight on our arms, the same muscle has lost its value.

Third Eyelid (Plica Semilunaris)

Scientists define vestigial structures as physical features that presented a clear goal but have gradually lost their utility through evolution. The third eyelid is one such example, which was utilized by some animals to protect and moisten the eye. It may continue to exist on your face, but it cannot move or provide protection.

Darwin’s Tubercle

Various anthropologists believe that Darwin’s tubercle, a small bump on the ear’s outer rim, helped primates better detect direction or amplify distant noises. But as time passed, ear mobility became less important, and the feature lost its function. Roughly 10 to 20 percent of people have it now, despite variations in shapes and sizes.